Contributing to the Development Guide

When most people think of contributing to an open source project, I suspect they probably think of contributing code changes, new features, and bug fixes. As a software engineer and a long-time open source user and contributor, that’s certainly what I thought. Although I have written a good quantity of documentation in different workflows, the massive size of the Kubernetes community was a new kind of “client.” I just didn’t know what to expect when Google asked my compatriots and me at Lion’s Way to make much-needed updates to the Kubernetes Development Guide.

The Delights of Working With a Community

As professional writers, we are used to being hired to write very specific pieces. We specialize in marketing, training, and documentation for technical services and products, which can range anywhere from relatively fluffy marketing emails to deeply technical white papers targeted at IT and developers. With this kind of professional service, every deliverable tends to have a measurable return on investment. I knew this metric wouldn’t be present when working on open source documentation, but I couldn’t predict how it would change my relationship with the project.

One of the primary traits of the relationship between our writing and our traditional clients is that we always have one or two primary points of contact inside a company. These contacts are responsible for reviewing our writing and making sure it matches the voice of the company and targets the audience they’re looking for. It can be stressful – which is why I’m so glad that my writing partner, eagle-eyed reviewer, and bloodthirsty editor Joel handles most of the client contact.

I was surprised and delighted that all of the stress of client contact went out the window when working with the Kubernetes community.

“How delicate do I have to be? What if I screw up? What if I make a developer angry? What if I make

enemies?” These were all questions that raced through my mind and made me feel like I was

approaching a field of eggshells when I first joined the #sig-contribex channel on the Kubernetes

Slack and announced that I would be working on the

Development Guide.

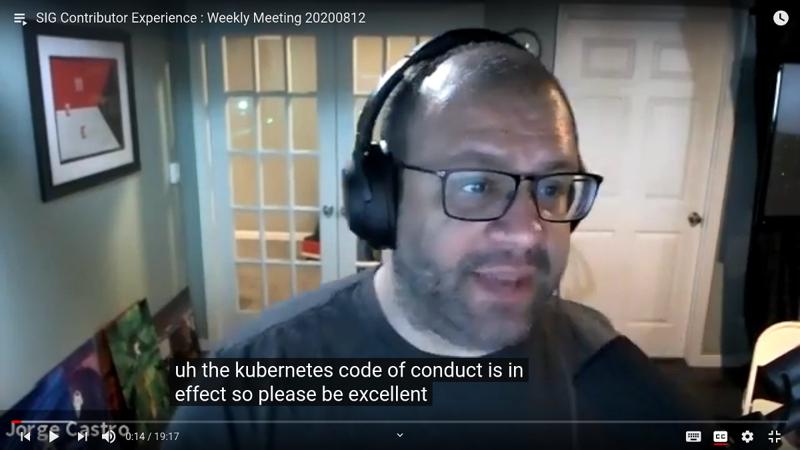

"The Kubernetes Code of Conduct is in effect, so please be excellent to each other." — Jorge Castro, SIG ContribEx co-chair

My fears were unfounded. Immediately, I felt welcome. I like to think this isn’t just because I was working on a much needed task, but rather because the Kubernetes community is filled with friendly, welcoming people. During the weekly SIG ContribEx meetings, our reports on progress with the Development Guide were included immediately. In addition, the leader of the meeting would always stress that the Kubernetes Code of Conduct was in effect, and that we should, like Bill and Ted, be excellent to each other.

This Doesn’t Mean It’s All Easy

The Development Guide needed a pretty serious overhaul. When we got our hands on it, it was already packed with information and lots of steps for new developers to go through, but it was getting dusty with age and neglect. Documentation can really require a global look, not just point fixes. As a result, I ended up submitting a gargantuan pull request to the Community repo: 267 additions and 88 deletions.

The life cycle of a pull request requires a certain number of Kubernetes organization members to review and approve changes before they can be merged. This is a great practice, as it keeps both documentation and code in pretty good shape, but it can be tough to cajole the right people into taking the time for such a hefty review. As a result, that massive PR took 26 days from my first submission to final merge. But in the end, it was successful.

Since Kubernetes is a pretty fast-moving project, and since developers typically aren’t really excited about writing documentation, I also ran into the problem that sometimes, the secret jewels that describe the workings of a Kubernetes subsystem are buried deep within the labyrinthine mind of a brilliant engineer, and not in plain English in a Markdown file. I ran headlong into this issue when it came time to update the getting started documentation for end-to-end (e2e) testing.

This portion of my journey took me out of documentation-writing territory and into the role of a

brand new user of some unfinished software. I ended up working with one of the developers of the new

kubetest2 framework to document the latest process of

getting up-and-running for e2e testing, but it required a lot of head scratching on my part. You can

judge the results for yourself by checking out my

completed pull request.

Nobody Is the Boss, and Everybody Gives Feedback

But while I secretly expected chaos, the process of contributing to the Kubernetes Development Guide and interacting with the amazing Kubernetes community went incredibly smoothly. There was no contention. I made no enemies. Everybody was incredibly friendly and welcoming. It was enjoyable.

With an open source project, there is no one boss. The Kubernetes project, which approaches being gargantuan, is split into many different special interest groups (SIGs), working groups, and communities. Each has its own regularly scheduled meetings, assigned duties, and elected chairpersons. My work intersected with the efforts of both SIG ContribEx (who watch over and seek to improve the contributor experience) and SIG Testing (who are in charge of testing). Both of these SIGs proved easy to work with, eager for contributions, and populated with incredibly friendly and welcoming people.

In an active, living project like Kubernetes, documentation continues to need maintenance, revision, and testing alongside the code base. The Development Guide will continue to be crucial to onboarding new contributors to the Kubernetes code base, and as our efforts have shown, it is important that this guide keeps pace with the evolution of the Kubernetes project.

Joel and I really enjoy interacting with the Kubernetes community and contributing to the Development Guide. I really look forward to continuing to not only contributing more, but to continuing to build the new friendships I’ve made in this vast open source community over the past few months.